Sine Ducibus

An essay on meeting the climate challenge in the absence of global leadership.

“Sine Ducibus” literally means “in the absense of leaders”. This essay was originally a proposal to a leading impact investor to fund a bottom-up approach to addressing the climate challenge. The irony is not lost on me that its failure to be funded is at least in part due to the fact that this person is one of the leaders my colleague Mayank Malik and I were implicitly criticizing when we wrote this.

National and global institutions have failed to address the principal problems facing humanity today. Whether we consider political dysfunction, social inequality, economic instability, technology inequity, or global climate change impacts on local communities, the existing national framework for the government of society is evidently unable to meet the demands of today’s world. The crush of converging crises today; e.g, climate change impacts, social unrest, technology consolidation, health crises, and emerging nationalism is forcing us to ask basic questions about what is the right thing to do now. We lack the framework in which to both ask these questions and act on the answers we come up with. There is no better time for change than when the existing frameworks have collapsed and there is no obvious replacement waiting to take over. We can and must act now, and we need the tools to do so.

Research over the past 20 years on the modeling and simulation of complex adaptive systems has shown that we can successfully model very complex systems from the bottom up. These simulations demonstrate clearly that no single scientific, engineering, economic, business, or political discipline holds the key alone to solving our problems. Instead we now rely on highly multi-disciplinary teams to collaborate as they create a wide variety of interoperable models and components that help us forecast how highly complex systems might evolve, given a particular set of initial conditions and an evolving set of boundary conditions. Agent-based simulation technology, supported by large-scale data platforms, has been successfully applied to macro- and micro-economics, electric power systems, military operations, and many other environmental, technical, social, political, and economic problems. Data-driven agent-based simulation stands ready to be scaled to the level of modeling global economic, political, technological, environment, and social systems and help us gain insight into how these systems would evolve were we to change fundamental aspects of how they behave and interact in a changing climate and degraded environment.

We believe we must use data-driven and agent-based approaches to model how alternative global institutional frameworks, technologies, business models, social norms, and climate scenarios co-evolve over periods of years to decades. The development of such a modeling system is a significant scientific, economic, and engineering challenge. But there is already a community of researchers worldwide who are working on parts of such a solution. They can bring this community together to develop the tools needed to answer the question of whether (1) there exists a quasi-stable combination of the social, political, business, and technology components sufficient to respond to the major challenges we face today, and (2) whether there exists a set of initial conditions necessary to ensure we can reach this new dynamic equilibrium.

Success in any large-scale program for change is driven by the alignment of incentives: any barriers to change can be overcome if a dominant coalition can be found for which the incentives to adopting the new regime overwhelms the incentives for preserving the old regime. The collapse of today’s dominant institutions in the wake of their failure to mitigate the impact of climate change, the resurgence of nationalism, a lethal pandemic, and the collapse of the global economic trade networks and global governance has created an opening for a new model of local and global governance supported by new local and global institutions. The question we must answer is how we are to design and govern these new institutions so that they embody the true will of the people they represent, rather than being subjugated to the will of and vulnerable to exploitation by a privileged few who have the means to use new technology, emergent crises, and the levers of economic power to usurp and corrupt the scientific and popular authority needed to effect change and maintain a long term sustainable future.

We are not proposing what this new system of local or global governance is, nor do we claim to have designs to even suggest one. Rather we suggest that we need tools that will allow a community of thoughtful, resourceful, and courageous local leaders from around the world to devise frameworks that satisfy certain essential requirements, most of which have yet to be clearly and precisely defined. In this post, we can only suggest a rough outline of what we believe the tools should allow us to consider.

Philosophical Approach

The tools we propose to create to study alternative frameworks must address the following framework components.

-

Governance: International political and trade bodies, transnational corporations, and leading nations have all failed to provide necessary leadership. They all have shown themselves to be susceptible to the influence of disproportionately empowered individuals and minority coalitions at the expense of the majority of the world’s population. The dynamics which give rise to this kind of disproportionate distribution of power and influence need to be modeled in any simulation environment that claims to enable the study of how changes in the political governance, social media, technological innovation, international trade policy, and environment regulation can affect global welfare.

-

Urbanization: The growth of megacities worldwide amplifies many of the adverse effects we see in international policy, society, economics, and technology. However, the existence of the amplified adverse effects suggests that there exists the potential for amplified beneficial effects as well. It will be vital for the simulation tools to represent and reveal the impacts of these effects.

-

Technology Maturation/Adoption: Technology maturation and adoption are a crucial aspect of any techno-socio-economic modeling framework. There are numerous examples of technology maturation/adoption scenarios that illustrate the degree to which this question is sensitive to exogenous inputs. For example, the growth of wind generation in the western United States during the 2000’s was strongly influenced by the collapse of the California PX and demise of FERC’s standard electricity market design. This in turn laid the foundation for the rapid growth of solar generation in the following decade. The interplay of technology adoption costs, market forces, financial incentives, and social forces drove this transformation more than any single factor alone ever could have.

-

Market disintegration and trade disintermediation: In many scenarios we find that vertical and horizontal integration is counterproductive, inhibits innovation, leading to low resilience at one end of the spectrum and inefficiency and unproductive asset utilization at the other end of the spectrum. In addition, global and local trade networks are constantly changing in response to changing regional conditions. It will be important for the simulation framework to capture both of these effects simultaneously, in order to reveal how the dynamic equilibrium from the tension between these affects outcomes over time, particularly in the wake of rare large events.

-

Local/Indigenous Communities: Many solutions can and should be explored to address outlying and indigenous communities where the majority of natural and renewable resources are located. Considering the local responses of and contributions by these communities to resource exploitation requires their engagement. Models must capture the salient features of how this engagement unfolds in time and whether communities are subjugated to, support, or lead change in their region. One important concept that is often lacking in models but needs to be represented appropriately, is the role of commons. We often hear about the “tragedy of the commons”, which has largely been debunked since it was first introduced without supporting evidence in 1968. But we rarely see analyses that examine how a commons and the rules governing its use contribute to an outcome. More novel ideas have since emerged with regard to natural resource management, some of which depend on technologies like cryptocurrencies, some on social mechamisms like social-media activism, and some on institutional frameworks including the assignment of personhood to natural resources in the same manner that some countries assign personhood to the companies that exploit those resources.

-

Valuing Long-term Global Impacts: One of the more significant modeling challenges we face in mitigating climate change impacts is how to value long-term costs with respect to short-term gains. The net present cost of a metaphysically certain climate disaster 50 years hence is evidently far less than the risk-free returns on investment of a project that contributes to the inevitability of that disaster. Clearly our models for what is worth investing in are deeply flawed, and as a result, business models that are obviously detrimental to the global ecosystem in the long run continue to be financed in the short run. The models we propose to build will allow us to incorporate long-term value propositions using various methods, such as carbon taxes, cap-and-trade markets, and other novel approaches.

The approach we propose is to create domain-specific agent-based models that can interact with each other within a global economic, political, business, technology, social, and environmental landscape that continually evolves in response to change. This agent-based simulation will permit us to study how different frameworks impact outcomes such as mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating the impact of climate change on local communities, and mitigating the concentration of political, technical, and economic power in the wake of ever more frequent crises and major events.

We do not believe in or even condone the use of purist economic theory, or any particular economic orthodoxy. For example, we do not believe that a simulation should implement either purely Keynesian nor purely Austrian School economics, nor any other economic model per se. Rather the simulation must allow for the pendulum to swing between a tendency for regional, national, and international policies to be driven toward or away from different economic philosophies in response to changing conditions.

Grassroots by design

For the majority of governance systems in the world, measures of success and failure are rooted in the idea of Market Fundamentalism. Economic growth is the chief measure of success. Societal benefits are determined primarily by economic returns and ranking. But deep down we know this idea is seriously flawed because it fails to value life, liberty, happiness, privacy, and health as equal, if not more important contributors to human welfare. Like the proverbial drunk searching for his keys under the streetlamp because the light is better, economics has devised national performance metrics like GDP, not because they more accurately reflect what we believe is important, but because they are easier to measure and they measure what leadership care about, i.e., metrics that keep them in power. In a world where the economy is predicated on eternal 3% growth (which is of course physically impossible), we have no option but to assume that environmental damage, harmed human health, and lost cultural diversity come at no cost, and have no consequences. We treat these all as cost-free commons in infinite supply. The tragedy of the commons exists not because it is inevitable but because we have adopted a value system that allows for no other option. As a result none of these values is sustained in the long-term, and the loss of sustainability is literally killing us. Therefore, the first step to solving this problem is devising a paradigm that more accurately accounts for the value of what is important to us.

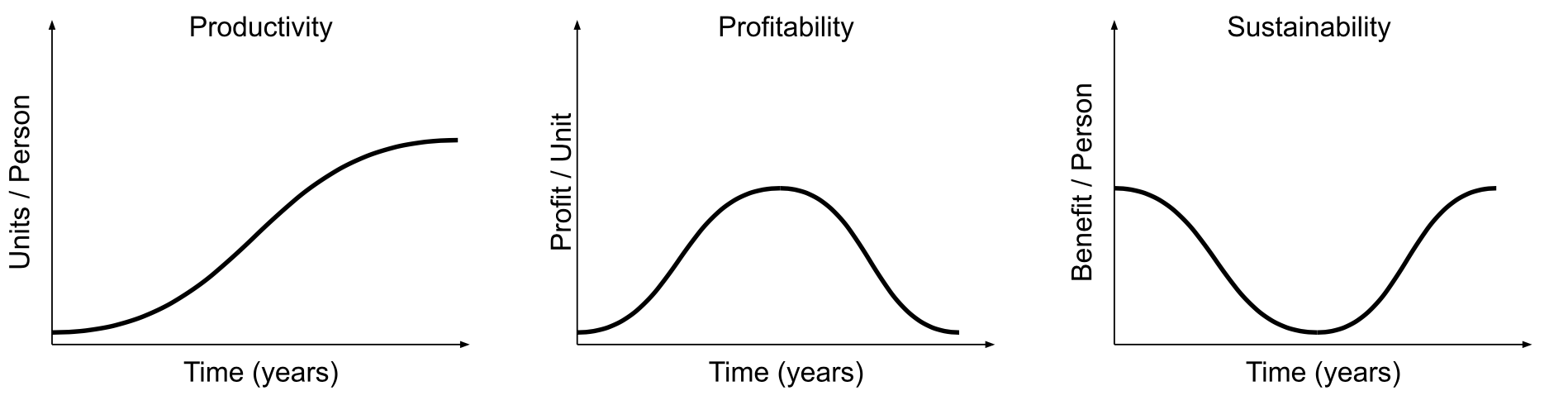

Figure 1. Grassroots by design sustainability model

The basic approach to quantifying sustainability we propose is summarized in Figure 1. According to this model, as a technology matures or a resource is exploited, overall productivity increases. However, profits are greatest only during the period when the users of the technology or resources have a comparative advantage over those who do not have equal access to it. This is what motivates constructs which enshrine inequality. However, over time access inevitably becomes more equitable and profits diminish as competition increases. Conversely, in the rush to exploit the comparative advantages while they last, the negative consequences of technological utilization or resource exploitation are sublimated. As a result, the sustainability of the resource or benefits of using the technology at first diminish before rising again later when equity is finally achieved.

This concept is essential to understanding the role and importance of being grassroots by design: if the rules and systems are in place to balance profitability and sustainability, then we can do more to ensure and protect the welfare of those who would otherwise be adversely affected by the transition. We can then mitigate the negative effects that accrue when the welfare impacts are external to the profit calculations that drive the adoption of the technology or the exploitation of the resource.

So how do we realize grassroots by design? In our model, it is simply the ability to quantify the value of long-term externalities explicitly at the same time and in the same way that we quantify the short-term profits. When an oil company obtains a drilling lease on land occupied by an indigenous population, it is not the national government in a far-away capital that decides alone what that lease is worth based on an auction designed for the buyers. The local community not only has a say in the cost of the lease, but shares significantly in the revenues generated by it and how those revenues are invested. This revenue is not a charity from the national government that is weaponized to control the local community. Rather it is a natural birthright they retain by virtue of their residence and stewardship of the land from which the resource is extracted. In addition, the extra costs to the company exploiting the resource mitigates the rush to profits, and ensures that sustainability is a non-trivial factor in the final analysis.

Deep anti-disciplinary solutions

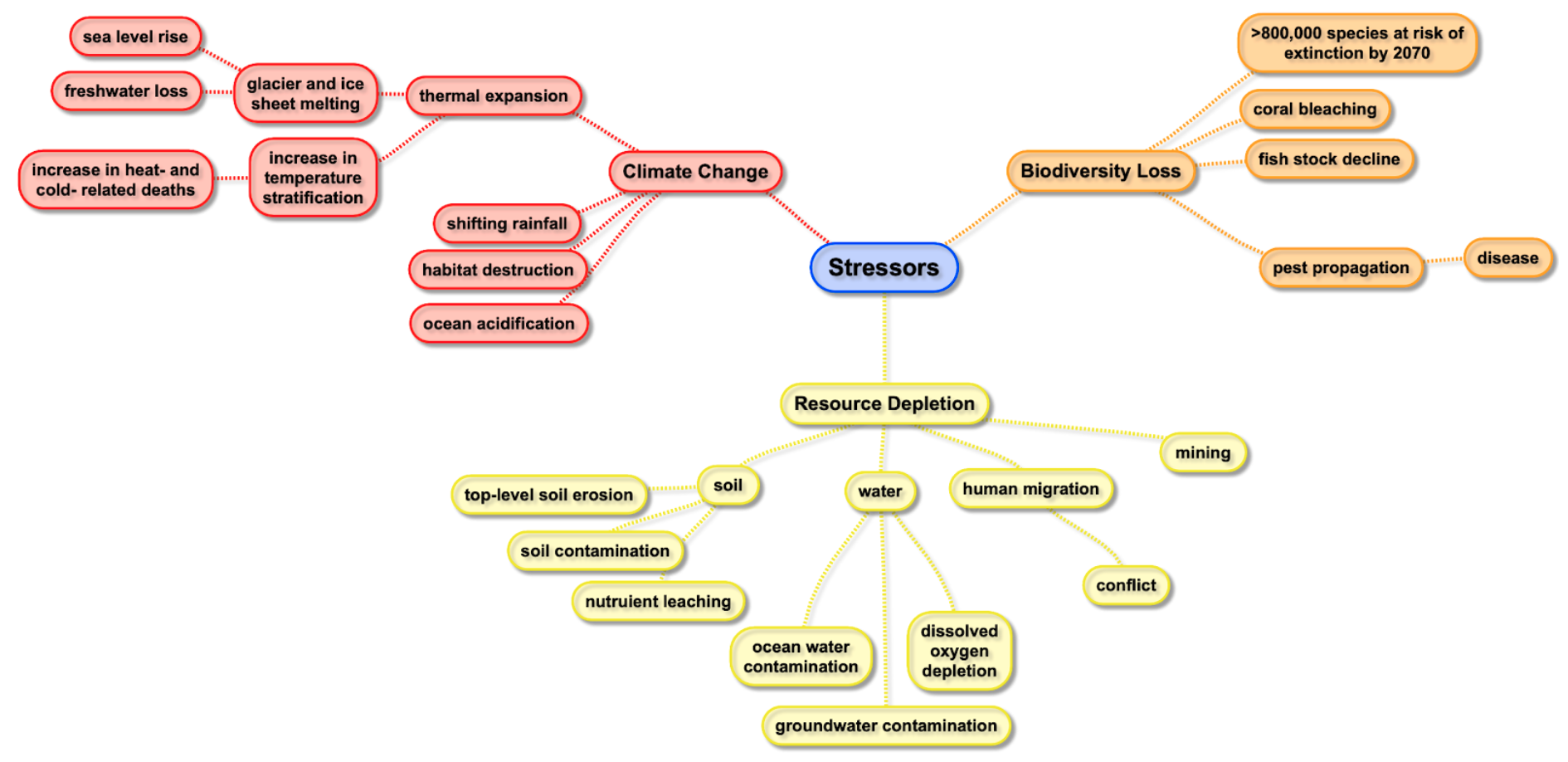

Climate change is only one of the stressors on our ability to thrive. The two other stressors are resource depletion and biodiversity loss. Each stressor, when left unaddressed or unchecked, tends to further exacerbate the effects of the other two, creating a dangerous feedback loop. Therefore it is imperative that solutions to climate change or climate adaptation also address resource depletion and biodiversity loss. To achieve this, it is important to create a taxonomy of phenomena that defines and classifies the feedback loops between various components of each stressor.

Figure 2: Stressors that affect global welfare and outcomes

Consider the mindmap of the three stressors in Figure 2. We are aware that climate change is going to result in thermal expansion and glacier and ice sheet melting, which in turn cause sea level rise. Solutions to the sea level rise problem may include raising cities levels above sea level, building flood water channels, installing stormwater pumps, upgrading sewage systems etc. Although effective in their own right, these solutions are shallow solutions since they fail to account for interdependence on and feedback loops with other stressors such as resource depletion. So let’s re-examine sea level rise with regard to resource depletion. Sea level rise will cause aquifer contamination, reducing fresh water availability for agriculture, thereby constraining our ability to support thriving populations in affected areas. Lack of food problems can be solved in one of two ways: 1) transport food from elsewhere, and 2) move people to where food is. Assuming the food supply chain is using a fossil-based transportation system, we may be contributing to the problem more than to the solution. On the other hand, mass migration of humans may trigger human conflict and civil unrest. Neither are desirable outcomes.

When we approach this problem from the perspective of a feedback loop between climate change and resource depletion, it’s hard to deny that the solution is going to be anti-disciplinary or at least multi-disciplinary. It will require experts from various disciplines to come together - civil engineers to make coastal cities more resilient, farming communities to exploit water-efficient farming techniques like hydroponics and aquaponics at scale, transportation engineers to design energy efficient supply chains, and politicians to develop governance systems, protective measures, and subsidies that prevent civil unrest resulting from resource scarcity.

There are many interdependencies and feedback loops between various climate change outcomes. A simulation system would help identify these interdependencies, quantify their sensitivities to decision variables we can affect, allow us to run what if scenarios, and conduct cost-benefit analyses for various competing solutions.

Central Ideas / Key Principles

How do we protect our natural resources from short-term profit-driven exploitation while ensuring that our solutions are not an impediment to economic activity? Alternatively, how do we influence individual behavior to align with global sustainability goals? Borrowing from indigenous experience, the answer to this question revolves around two concepts – Stewardship and Balance. Both stewardship and balance have played a central role in indigenous cultures around the world.

Stewardship articulates the idea of guardianship of land, water, and air. In Māori culture for example, stewardship embodies the idea that there is no distinction between a people and their environment. In 2017, New Zealand granted the status of legal personhood to the Whanganui River, the third-longest in the country and, the indigenous Māori believe, a living ancestor of their people. Therein lies a potential solution to the resource overexploitation problem. Corporations around the world already have personhood. Why shouldn’t our natural resources like rivers, mountains, and seas? Imagine a river, managed by a community-elected board of directors with fiduciary responsibility for its long-term survival, owning stock in a bottling plant that exploits its resources. Imagine distributing the river’s rights to local non-profit organizations who act on behalf of the river to prevent overexploitation. By establishing an equitable distribution of responsibility and allocation of benefits, we can achieve balance without directing it from central authority.

We must learn from indigenous communities around the world and adapt their principles to modern society, capitalism, and available technology.

The Process

The development of a tool to model and simulate such systems requires a comprehensive redesign of the existing tools we use to model complex adaptive systems in economics, energy, and social systems before we can integrate all the disciplines we seek to incorporate.

- Define layers of climate adaptation

- Develop a taxonomy and classification system to identify interdependencies and feedback loops between various stressors - climate change, resource depletion, and biodiversity loss

- Define how ideas of stewardship apply to each of the layers of climate change

- Define global objectives detailing what change we want to see for each layer of climate change

- Create anti-disciplinary solutions and integrate multi-disciplinary solutions that influence individual choices by aligning individual incentives with global objectives defined in #4. This is the big lift of this framework.

- Gamify stewardship to model global collectivist cultures and make it appealing to those for whom this is a new concept.

- Augment measures of human welfare to include economic, health, social, political and emotional factors.

- Teach innovators, entrepreneurs, and investors how to use this new tool to think about how their plans and actions will play out in possible futures.

Next Steps

We must gather and fund a team of social, environmental, legal and political scientists, economists, and engineers who will assemble, verify, and validate this new global modeling framework so that governments, impact investors, philanthropists, and innovators have a tool they can use to study how their frameworks will affect the world and interact constructively and destructively with other frameworks under consideration.